Digital Assets in the Context of Nascent Markets in History

Digital Asset markets are in their infancy and are experiencing growing pains similar to those of the today’s major asset classes. To learn how early markets behave, we examine the rise of equities in 17th century Europe, the US stock market bubble of the 1920s, the evolution of emerging market investment in the 1980s, and, most recently, high-tech venture capital.

Key Takeaways

Nascent markets are messy. The promise of outsized financial gain causes lessons of the past to be quickly forgotten and prior mistakes readily made again.

The circumstances of market cycles vary over time, yet possess a crucial commonality: emotions override measured rationality, leading to temporary disorder.

Markets and investors must suffer through a mistake-laden maturation process. Setbacks and imperfections during this period are not an indictment of the underlying technology.

Regulation is not a substitute for investor discipline, but is necessary for operational clarity in the digital assets space.

Participation in early markets rewards long-term time horizons, disciplined decision-making, and patient navigation of novel risks.

Early Markets are Messy

Digital asset markets are young and they are messy. However, while investors may sometimes behave as though they are in one, they are not a casino. Like many other inventions and innovations that experienced high expectations and volatility, we strongly believe there is actual value in cryptocurrencies and other digital assets, and that with proper execution, investors can take well-compensated risks to earn commensurate rewards.

Investors can better understand the risks and rewards of digital assets by comparing them to now-established asset classes, and investors frequently do so, citing events in recent history. Under appreciated are the comparisons to when those asset classes were in their own nascency, as digital assets are now. At the same time, one must consider not just how markets have evolved, but also how human behavior may not have. Furthermore, digital assets are a global phenomenon, and can’t just be thought of through the lens of contemporary, developed market equities.

We explore in this piece how the revolution in digital assets can be seen in light of the early days of developed market equities, emerging markets, and venture capital – and the booms and busts that have accompanied them all. We also consider the positioning of blockchain technology vs other breakthrough technologies of the past, and what that means for early investors. In particular, while the market for digital assets shares many of the hallmarks of other early markets, it remains unique in that the technology and the means of investing in it (blockchains and digital assets, respectively) are inextricably linked.

Our look at the past is not to rationalize or justify any of the mistakes of today’s digital asset markets. It is sad and frustrating to see so many lessons from history having to be re-learned. But it is also not the first time in history where wisdom of past follies has seemingly been ignored. Our strong contention is that neither the asset class nor the technology have ever been the true fault. Dismissing digital assets and blockchain technology for the mess of the early market would be akin to having dismissed stocks as a concept soon after their invention, or blaming the internet itself for the tech bubble.

Equities

The recent wave in cryptocurrency investment has often been likened to the dot-com bubble that burst in the early months of the new millennium (2000). The similarities are certainly there. Both bouts of enthusiasm were around the potential of new network technology: the Internet then, and blockchains now. The 90s run up in internet tech and the 2021 run up in cryptocurrencies were also both fueled by declining interest rates that drove huge increases in startup formation and venture investment. But the crucial difference to us is that the asset class (stocks) was decidedly not new during the dot-com bubble, and even the investor landscape already looked quite similar to today.

Formation of the Dutch East India Company, 1602, (c1870). Artist: JH Rennefeld. The Print Collector / Heritage Images.

The humble concept of the “stock” dates all the way back to the early 1600s, when the Dutch East India Company listed its shares on the Amsterdam stock exchange: the first and only company to do so for many years. Over the ensuing decades, more companies followed suit across Europe.

Consider that this means that stocks are an asset class over 400 years old, and that despite those centuries of accumulated experience, speculation, fraud, mania, and crashes persist as facets of the market...

To draw some closer parallels to digital asset markets today, let us consider the early markets of the 17th and 18th century in Europe, as well as the early 20th century in the US. While the latter does not mark the birth of the US equity market, the early 1900s are early in the context of markets that were beginning to resemble the the corporatized, industrialized world of today.

17th-18th Century Europe: The Origin of Equities

The first equity markets looked quite different from the efficient (relatively), organized markets we have today:

Equity issuance was much more concentrated than in modern times, largely coming from a handful of trading and finance companies, many of which were state-chartered.

Exchanges, while organized, were essentially members clubs of individuals investing on their own account or facilitating trades for others. While the exchanges sought to control the quality of their membership, there were few rules.

Standardized financial reporting was non-existent.

Largely, equities were owned by individuals and not by institutions – and the concept of “professional” investment managers was not yet well established even with regards to debt instruments, which had been around for considerably longer.

Valuation techniques for stocks were also relatively primitive at the time (Rutterford 2004), more so reflecting bond valuation methods of the time than any distinct advancement.

While the structural differences to today are apparent, the fundamental similarity of investor and company behavior across time is remarkable, as we will explore.

The very first stock, that of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), is a fascinating case study from which to draw parallels to today’s digital asset markets. A narrative of this tale is relayed in Robeco’s 2018 publication A Concise Financial History of Europe (authored by Jan Sytze Mosselaar), which in turn draws from the studies in Lodewijk Petram’s book The World’s First Stock Exchange. Following VOC’s offering of shares in 1602, Mosselaar writes:

“Like most modern stocks, the VOC’s share price was quite volatile. Things started well and the price rose to 140% in 1606, and to as high as 200% after false rumors that the city of Malacca had been conquered, supposedly giving the Dutch control of the Strait of Malacca, an important sea lane close to Indonesia. But in the years that followed, the stock experienced severe setbacks, eventually falling all the way back to 130% in 1620. It wasn’t surprising that investors started to complain. The company didn’t pay out any dividends, it was not clear whether it was profitable, and it spent considerable sums of money on military operations fighting the English and the Portuguese in Asia. In 1613, fourteen shareholders officially protested about these expenses, but this had little effect.

In April 1610, the company finally paid out its long-awaited first dividend. But again, the shareholders were not happy, and for good reason. Because the VOC badly needed to use its capital overseas, it decided to pay out dividends in spices. Every shareholder received 75% of the nominal value of their holdings in mace. Percentage-wise, this was a good dividend. This was followed by a 50% dividend in pepper in November and finally, 7.5% in hard cash in December. But because of the sudden abundance of these spices on the market, the real dividend in cash terms turned out to be lower for most shareholders.

In total, the VOC paid out a total of 200% in dividend in the period between 1602 and 1622. Not bad for a start-up company! However, its shareholders were far from impressed. Inflation ran at 6%, they had no idea whether the company was making good profits and in 1612 they were asked to participate in an insurance program to guarantee the continuity of the company. As the company didn’t issue any additional capital after its 1602 IPO, it had to borrow money from different sources. From 1622 onwards, the company issued six-month bonds to finance its short-term operations. Later on, it started to borrow money from the Bank of Amsterdam. In the 17th century, as the company was generally in good shape, these debts were repaid in time and didn’t create a problem for the VOC and its creditors. Moreover, things started to improve in the 1620s. The company was growing fast, profits were rising and dividend payouts became more structural from 1630 on.”

Investors endured nearly two decades of uncertainty before the VOC reached financial stability. The dividends paid in spice (which in turn flooded the market with supply of spices) amusingly call to mind the “staking” programs of many tokens, while the lack of clarity on profitability remains a sticking point for many Web3 projects.

Jonathan’s Coffee House, London, 1763. ‘Jonathan’s Coffee House, or an analysis of Change Alley, with a group of characters from the life’. Foreigners discuss business in Jonathan’s Coffee House; Britannia swoons on the left and a devil views the scene with glee on right. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.

Despite the growing pains, the concept of stock issuance and ownership grew in popularity. The innovation of the publicly listed stock was highly attractive to companies, who could efficiently raise capital in a new way, as well as investors, who stood to make gains in excess of the bond markets. The idea quickly spread from The Netherlands to England. However, stockbrokers were seen as a rowdy and unscrupulous bunch, and their presence was not allowed at the Royal Exchange, which, as the site of various goods trading, would have been a natural home. Instead, the brokers began trading in informal venues such as Jonathan’s Coffee House or Garraway’s coffee house - actual cafe-type locales / social clubs that became home to the first systematic trading of equity securities in London. These social establishments ultimately evolved and formalized to become the London Stock Exchange (although not until 1773).

Meanwhile, the stock market grew rapidly, and counted around 150 companies by 1695 (Mosselaar 2018). This early boom became known as the London IPO craze of the 1690s, and was accompanied by a boom in patent issuance, which were perhaps deemed to signal legitimacy or value. However, during the IPO craze, many companies of questionable validity issued stock and speculation was fueled by “stock jobbers” (market makers trading with their own capital) who talked their own book to make profits, often relying on misinformation to steer markets in their favored direction. In many ways, it was much like the dot-com bubble of the 1990s.

Unsurprisingly, the period ended in 1696 with a crash that vaporized 70% of listed companies. The English government somewhat belatedly took action, limiting the number of market makers, abolishing proprietary trading, and reining in high commissions on trades. But the regulation was not enough to prevent future speculative bubbles such as the Mississippi and South Sea Bubbles in the 1720s.

A wind trader sits on a bag of shares held high only by the wind, 1720. Origin: Northern Netherlands. From The New York Public Library.

Those next periods of excess again bear similarities to other bubbles, future and past. So pervasive were the questionable fundamentals of stocks in the early 18th century, that contemporaneous commentators in the Dutch Republic dubbed the greedy actions of investors and stock issuers as the “windhandel”, or windtrade (named for the ephemeral nature of the newly listed companies). The best known of the bubble stocks of the time were John Law’s Mississippi Company in France and the South Sea Company in England. Both were based on trade monopolies and financial innovations (including conversion of debt-like liabilities into equity), and both pushed too far with their financial engineering and ultimately failed to realize their expected potential.

While the fascinating details of the rise and fall of these companies goes well past the scope of this piece (for more information see Mosselaar 2018), one interesting consequence of the South Sea Bubble to consider was the passage of the Bubble Act in England in 1720, which banned new public listings of companies without a royal charter (which the South Sea Company already had). Although this may look like well-intentioned government regulation, the act was more like anti-competitive special interest legislation (Harris 1994), passed to protect the bubble in the South Sea Company’s stock price from incumbent bubble companies by limiting competition for investors’ capital. Of course, it ultimately had the opposite effect, as the crash in prices of other stocks fed into negative sentiment around the South Sea Company itself, resulting in a broad spread price collapse.

Takeaways

As we can see from this condensed overview of the earliest of stock markets, investor behavior carried the same hallmarks as today: There was greed, fear, fraud, market manipulation, and poorly constructed regulatory responses. While the underlying companies of early equities were quite different from the blockchain-based enterprises of the crypto market, the human component of both markets are remarkably similar. So what can we learn from this period of early financial experimentation?

First: It was not the technology or business proposition of the companies themselves that caused the trouble. International trade as a business was not the issue. What was at issue was the unquestioning belief in the vastly overstated potential of the companies’ endeavors, sustained by the greed of investors, and the lack of any fundamental consideration regarding the value of the stock. We see the very same in the bull and bear cycles of the crypto markets today, and continue to see it in modern day growth stocks as well. As we have discussed in our previous work (Diversification Part II: Why Crypto?), we believe blockchain technology carries meaningful potential, and that digital assets will be the key to capturing the value they create. Similarly, there is good fundamental reason to be excited about the prospects of many growth stocks in the public equity market today. But, broader investor sentiment is often driven more by short-term price action and biased commentary (i.e. the Twitter sphere) than careful consideration of the long-term potential of the space. Separating the signal from such noise is the task of the serious investor.

Second: It was not the financial instrument itself that was at fault. The publicly listed stock as a concept was clearly revolutionary for raising capital to finance growth and innovation, and offered investors higher returns than fixed income instruments. However, unscrupulous underwriting and investment drove speculative mania that divorced prices from fundamentals and gave a free pass to companies that clearly lacked substantive businesses. The parallel to today is clearly that digital assets themselves are not the issue. Cryptocurrencies, tokens, and other digital assets hold revolutionary potential for the networks they empower and secure, and the stakeholders who own them. Digital assets are a financial innovation that capture much more than a slice of profits in a business. They are participatory, network-driven assets that give users of a system a stake in the success of the system, at once securing the network and incentivizing growth. As such the value of the technological innovation of blockchains is inextricably linked to digital assets in a way that no other financial instrument has been linked to the business they finance.

Clearly, not all projects will succeed, and not all digital assets are well-structured. Arguably, the “killer” use case of blockchains and digital assets is yet to even be realized. That’s exactly what makes it an interesting, albeit high-risk investment. However, the pendulum of sentiment in early markets can swing quickly from blind euphoria to abject depression. This obfuscates the technology’s true potential and contuined progression, tempting investors to write the asset class off. Fundamentally, we believe that both the technology and the instrument show incredible promise, and it is the job of an investor to see through the gyrations of sentiment today and focus on the unrealized potential of tomorrow.

Third: Lack of established valuation techniques does not equate to an absence of value. A common complaint about the digital asset market is that nobody knows how to “correctly” value cryptocurrencies, tokens, and the like. However, this implies that there are “correct” or “accurate” ways of measuring the intrinsic value of existing assets. This is not necessarily the case. While certain asset classes have accepted methodologies, they are not uniformly applied nor exhaustive. The collective wisdom on valuation is a function of time, availability of data, and the creativity of those doing the research. Therefore, it is unwise to conclude that novel assets like cryptocurrencies have no inherent value simply because previously established valuation methods are a poor fit. Such methods have benefited from decades, or even centuries, of development, and were tuned to reflect the nature of the asset classes.

For context, Janette Rutterford explores the history of valuation techniques in her 2004 paper From Dividend Yield to Discounted Cash Flow: A History of UK and US Equity Valuation Techniques. Her work highlights how earnings-based valuation techniques are also relatively new – with dividend yield and book value being the predominant forms of valuation for early equity investors. Such an approach assumed equities were little more than riskier bonds – an assumption that was challenged in works by Smith (1925) and Fisher (1930), but not immediately widely accepted. Discounted cash flow valuation methods as applied to equities emerged even later, in the works of authors such as Preinreich (1932) and Williams (1938). (Rutterford 2004).

Cryptocurrencies, however, cannot be conceptually simplified to fit the mold of other asset classes. They exhibit a unique combination of equity-like and currency-like features, while also reflecting the exponential value potential inherent to networks (a la Metcalfe’s Law). Valuation methodologies continue to evolve across all asset classes, and a more defined understanding of digital assets valuation will solidify over time through the endeavors of insightful investors able to identify the most useful of the established concepts, combined with new, creative methodologies tailored to digital assets.

Finally: Patience is rewarded when you weather the volatility common to early markets. To illustrate, we can examine again the Dutch East India Corporation. Despite early troubles, the VOC lasted for nearly two centuries, and provided attractive returns in various periods of its history. The precise returns are difficult to calculate given data availability, but analysis by Lodewijk Petram, author of The World’s First Stock Exchange, suggests that investors that bought in with 100 guilders in 1602, saw their investment grow to just over 65,000 guilders by the end of the century, assuming reinvestment of dividends. This corresponded to an average yearly return of ~8.7%, which far exceeded the interest rates on bonds in the region over the period (Petram 2021).

NASDAQ 100 Price Index. NASDAQ.

The same can be said of later bubbles. Despite the bursting of the dot-com bubble, the NASDAQ 100 has still returned over 5500%, including dividends, since 1990, through 2022, despite the index losing over 80% of its value during the crash.

While assets can bubble, investing in good companies at good valuations (in the case of the early markets, in the absence of rigorous valuation, this generally just meant earlier and at a lower price) tended to offer good results to those who could weather the volatility. Patience pays off.

Early 20th Century United States: The Tipping Point to Regulation

From the last section, one might think that investors had ample opportunities to be humbled and learn from the folly of the early stock markets. This was not the case. We skip ahead to the early 20th century as evidence of this, not forgetting that between the 1700s and 1900s there were numerous other periods of stock market volatility to learn from as well.

To be clear, the early 20th century did not mark the invention of stocks (see prior section), nor the emergence of stocks in the US, nor the first boom and bust in American stocks1. But, when compared to the investment world of the later 20th century, the market of the 1910s and 20s arguably marked a tipping point for modern finance.

So what did the stock market look like in early 20th century USA? Notably, despite various booms and busts during the 19th century, the market still lacked substantive regulation – either of stocks markets or other financial activity. Up until that point, the most impactful regulations came in the form of the National Banking Act of 1863 and the Bankruptcy Act of 1898, neither of which dealt with securities regulation. Regulation was largely self-imposed, for example via exchanges like the NYSE.

A busy day on the curb market. Frank Craig 1912. From the New York Public Library.

The early 1900s also saw a rapid rise in the number of publicly listed companies, which grew from <300 pre-1900, to over 1,200 by 1930, using stocks on the NYSE as a proxy (O’Sullivan 2007). The expansion was even greater when considering the relatively bustling Boston and Philadelphia exchanges, as well as the informal New York “Curb” market and other New York trading markets.

Several industries helped drive this expansion, which reduced the dominance of transportation (railway) companies and shifted more weight in the stock market to Energy, Real Estate, and other Industrial companies. At the same time, individual companies themselves were growing rapidly, as modern management techniques emerged and companies became highly efficient vertically-integrated enterprises that captured economies of scale and scope (White 1990). The growth of US companies was also inextricably linked to the growth of the US economy amidst the post-World War I optimism of the “Roaring Twenties”, which cemented the US as the richest and most economically dominant country in the world.

The boom of the 1920s was not purely financial speculation. There was a legitimate emergence of new products and technologies, boosted by the advent of new managerial methods, organizational advances, and production methods. The automobile industry, for example, boomed in the 1920s as cars evolved from a luxury good to an attainable appliance for the middle class thanks to the assembly line innovation of Henry Ford. At the same time, electric grids expanded and brought power to the nation, the aviation industry experienced milestone advancements, radio emerged as the first mass broadcasting medium, and the “moving pictures” of the cinema became a staple of entertainment for all. This was all done in the context of corporations, which were not a new organizational structure, but were increasingly dominating the technical progress of the day.

These meaningful advancements stoked the enthusiasm of investors, and for good reason. To assess how investors were incorporating innovation into stock valuations, Tom Nicholas, a Harvard professor, does an interesting study through the lens of intangible capital2, measured by patenting activity (information on which is readily available for the time period). The accumulation of intangible capital has been cited as a driver of investors’ valuations of firms during the dot-com boom (Hall 2001), but it is difficult to assess for the earlier periods such as the 20s, which lack much of the financial documentation we take for granted today. Ignoring investors’ response to innovation gives a false picture of the extent to which high valuations were driven by pure animal spirts vs fundamentals.

Nicholas finds that investors in the 20s were indeed reflecting information on intangible capital growth in their valuations, their responsiveness to which led to large increases in stock valuations, which arguably fed back into encouraging the growth of such intangible capital. The long-term value of this intangible capital can be seen in the thousands of patents granted between 1920 and 1929 that were still cited in patent grants decades later (the period between 1976 and 2002 was studied). Nicholas’ full study is well worth considering, as it paints an interesting picture of investors’ changing attitudes towards innovation and intangible capital and the implications on stock valuations. But clearly, the important new technologies of the 1920s demonstrate that legitimate economic growth and innovation are still often at the core of what may appear to be purely speculative chaos.

Sadly, nothing gold can stay, and greed increasingly stoked markets as the 20s progressed. As has so often been the case, leverage added fuel to the fire, with some attributing the crash of 1929 to the tightening of margin requirements by banks which were becoming concerned about valuations (Borowiecki, Dzieliński, Tepper 2022). At the same time, investment trusts rose to prominence in the market, but were plagued by poor management, fraud, insider trading, and high leverage, which caused most of them to evaporate in the crash.

Sadly, nothing gold can stay 3, and greed increasingly stoked markets as the 20s progressed. As has so often been the case, leverage added fuel to the fire, with some attributing the crash of 1929 to the tightening of margin requirements by banks which were becoming concerned about valuations (Borowiecki, Dzieliński, Tepper 2022). At the same time, investment trusts rose to prominence in the market, but were plagued by poor management, fraud, insider trading, and high leverage, which caused most of them to evaporate in the crash.

So had investors learned from prior periods of exuberance that led to ruin? Arguably not. But what makes the 1920s crash particularly interesting is not just the fortunes made and lost, but the resulting legislation in subsequent years, in the form of the 1933 Banking Act, the Securities Act of 1933, and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Together these acts sought to substitute the hope that investors might learn from past mistakes with a formal codification of rules and regulations to address the more fraudulent and speculative aspects of the market that allowed the stock bubble to flourish in the late 1920s.

The first of these acts, The 1933 Banking Act, commonly known as Glass-Steagall, had a key provision which forced the separation of investment banking from commercial banking. The latter two acts were arguably more pivotal than Glass-Steagall (which was ultimately repealed in 1999). The Securities Act of 1933 regulated the offer and sale of securities at the federal level, and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (SEA) regulated the secondary trading of these securities. The aim of both acts was to increase financial transparency around securities by regulating their issuance and the exchanges on which they trade. At their core, the acts mandated certain disclosures from companies and operators in the securities space, thereby reducing fraud and market manipulation. To do so, the SEA authorized the formation of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which has the power to oversee securities, the markets there of, and the professionals (both individuals and companies) dealing in these markets.

Today, these laws and the SEC are of immediate relevance to digital assets, given the uncertainty of whether or not cryptocurrencies and other digital assets are securities, which would make them subject to regulation such as the 1933 and ‘34 Acts. At a high level, this would mean adherence to the disclosure requirements for securities listed on an exchange, which include (among many others): registration of those securities and detailed company financial disclosure. Whether or not digital assets are securities is beyond the scope of this publication, but many market participants are not against regulation and are anxious for clarity on how existing regulations apply or whether new ones will be written.

Takeaways

The takeaways of the 1920s are remarkably similar to the even earlier days: Technology was not the issue and the form of investment was not the issue. Quality companies, with valuable products or services, survived the mania and emerged better for it. Take US stock stalwarts such as IBM, Ford, General Motors, GE, and Coca Cola, that emerged in the early 20th century or earlier and have continued to create value through multiple periods of tumult. The same can later be said of technology companies that survived the dot-com era crash and have gone on to become some of the most lucrative investments ever (Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Oracle, etc.).

Human behavior is this constant in these episodes, and one of the first meaningful regulatory responses attempting to restrain it arose from the aftermath of the 1920s stock market episode. The Acts of 1933 and 1934 made significant strides in assuring that investors had more information upon which to base their investments, while also professionalizing the behavior of financial services firms. The extent to which regulation can successfully “fix” investor behavior was debated then as it is now.

A survey done by C. John Kuhn in 1937, published in the journal Law and Contemporary Problems, suggested that the prevailing opinion among institutional investors of the 1930s was that the regulations did little to impact their investment decisions. Perhaps this is not surprising given that this class of investors was already doing deep analysis on potential investments, and that arguably the regulation better served less sophisticated investors (at the time “institutional” investors, aka banks and insurance companies, made up <10% of shareholders per Goldsmith 1973). Another noted effect was that more offerings moved to the private placements market, which was accessible primarily to institutional investors, reducing the inclusivity of investment opportunities with regard to smaller investors. At the same time, investors worried about the impact of the Exchange Act on market liquidity, contending that price movements had become more erratic as market volumes and venues dropped.

These were relatively short-term reactions, however. Later work, such as that by Carol J. Simon (1989) examined the longer-term changes in securities markets and found that regulation did manage to lower the “dispersion of abnormal returns (investors’ forecast errors)” as increased information provided more explanatory power for price movements. However, Simon also examined the 5-year failure rates for IPOs on the NYSE and other US exchanges before and after the 1933 Securities Act and, found that only a small, and relatively constant, portion of IPOs on the NYSE failed both before and after the passage of the Act . However, the failure rate for non-NYSE IPOs did drop considerably. This suggests that self-regulation at the most prominent US exchange was largely effective even before the passage of the Act, but that less prominent venues were perhaps more unscrupulous and therefore saw improved quality of offerings after regulation.

However, it is difficult to come to a robust quantitative conclusion as to the impact of disclosure regulations. In Measuring the Effects of Mandated Disclosure (Ferrell 2004) the author discusses the challenges of measuring regulations’ impact. As such, we examine the qualitative angle again. Regulation was a key outcome of the 1920s episode, and could again be the next step in the evolution of digital assets, so what can we learn from the past in this case?

We believe one takeaway for sophisticated investors is that, as evidenced by future bouts of ecstasy and agony in US equity markets (1987, the dot-com bubble, the Great Financial Crisis, etc.), regulation itself cannot prevent losses and is no guarantee of safety. Digital assets, and the blockchains they are based on, are a rapidly evolving technology, with high expectations, trial, and error still characterizing the market. Regulation should not be expected to take this element of risk out of the market, just as it has not ensured that every security issued today is a good investment. Even the most legitimate of projects may still fail. Trial, error, success, and failure are all necessary for the maturation of the market, and are exactly the elements that provide the opportunity for distinguished returns for those willing to take the risk.

In the context of the broadly regulated financial markets of today, digital assets do also need clarity on the rules and regulations relevant to the asset class. Given the intricate dependence between blockchains and digital assets, such clarity is essential for the technology to even operate. The differences in the structure of many digital assets compared to existing securities warrant the market’s request of regulators to clarify how existing rules apply, and if not, codifying new ones to reflect the differences. But, don’t expect such rules to remove all the risk.

Emerging Markets

Emerging Markets provide another interesting look at the behavior of “nascent” markets, and the risks and rewards of EM investment exhibit remarkable parallels to investment in digital assets today. Economic promise, global competition, governance risks, legal ambiguity, and monetary policy are all critical concerns for investors in both asset classes. Emerging Markets are also one of the newer asset classes to enter investor portfolios, coming to prominence, as we know them today, only in the 1980s. Many of the countries making up the “Emerging” group of markets have of course existed for centuries, and many established markets today may once have qualified as “Emerging.” The exploration of the “New World” was in a sense the first investment in emerging markets and investment outside of the UK and Europe by individual investors was relatively common as early as the 19th century, when many popular pieces of investment advice advocated diversification, and suggested doing so geographically . At that time, investments in both stocks and bonds were available that offered exposure to countries across the world, from Central and South America, to Africa, Eastern Europe, and Asia (Rutterford 2016).

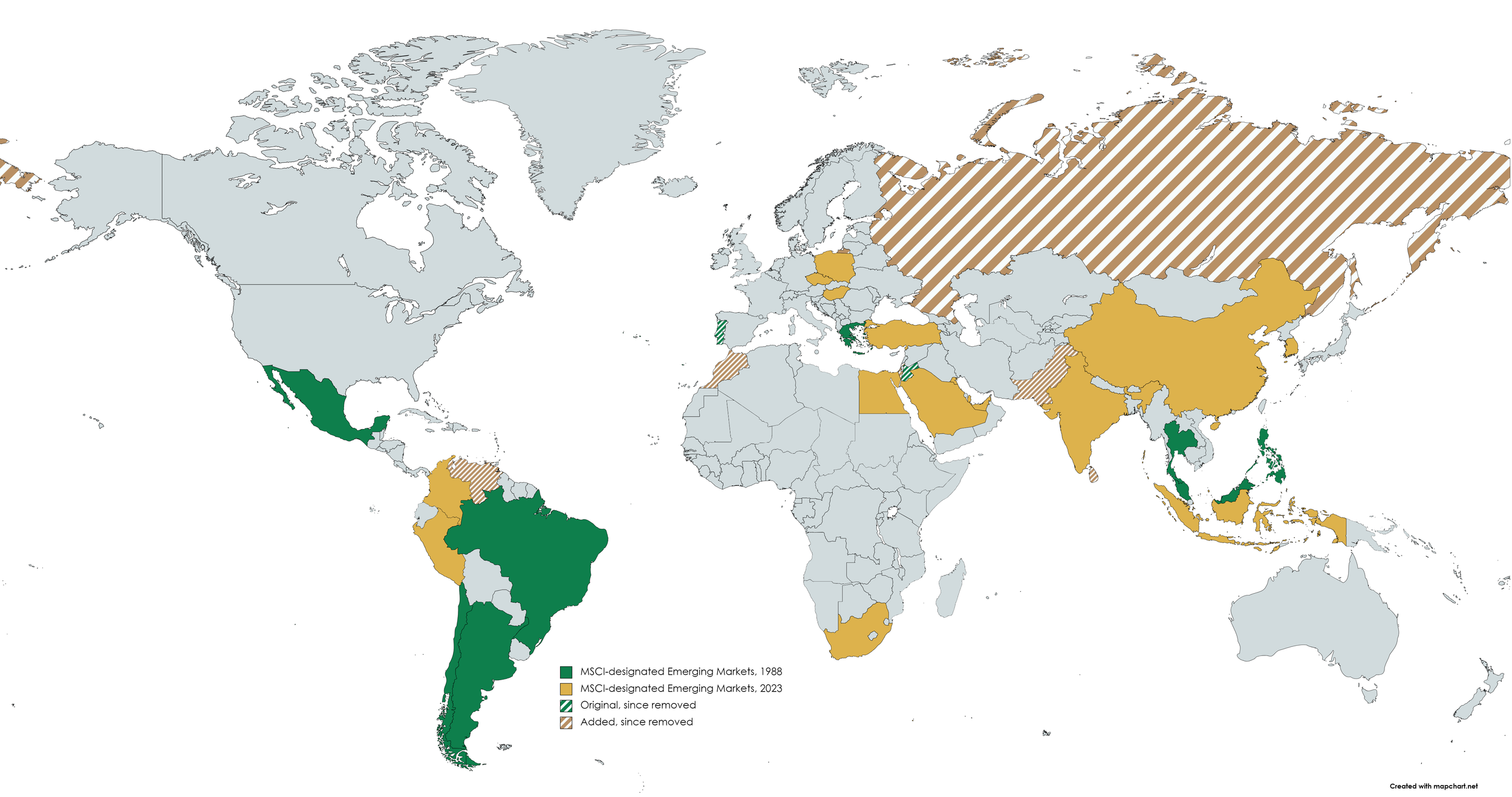

Map of the world highlighting original countries in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index (green), current (green, yellow), and countries added and removed over time (green and brown stripes).

The critical distinction of foreign investment in earlier centuries is that most of these investments would have been in economies or companies with direct ties to the UK or Europe, as a result of colonialism and imperialism. While still exposed to unique country-specific risks, the behavior of these economies and companies was dominated by foreign policy from developed market imperial powers. As such, the “Emerging Markets” we discuss today are generally the markets in countries after colonial rule, which largely ended in the aftermath of the World Wars (although some countries gained independence much earlier). This also generally puts the rise of EM parallel to the rise of institutional investors in the later part of the 20th century, making for a highly relevant case study of how institutions approach new, high-risk asset classes.

Conceptually, there has always been debate as to what makes a country an Emerging Market. The term itself was coined in 1981 by economist Antoine van Agtmael of the IFC, in a pitch to an investment bank for a new global investment fund for stock markets in developing countries (the less positive term originally proposed was simply “Third World”). Richard Sylla (1999) proposes a good definition of an emerging market:

Since emerging markets come in nation-state units, the first requisite of becoming one is national unification and political stability. The government of a nation that wants to become an emerging market must have legitimacy, and ideally it must offer protection to the human and property rights of its people. It also must offer the same protections to the foreign investors it hopes to attract to its economy, for attracting such investors is the sine qua non of an emerging market. Such a market typically has the human and natural resources-the labor and land of the classical economists-but it is more lacking of the third ingredient, capital, which accumulates as a country develops its economy. Becoming an emerging market implies that a nation convinces the world’s investors that its economic promise is great and that it can be realized more quickly with infusions of capital from outside the country, to the mutual benefit of the country and the foreign investors. At its heart, the concept of an emerging market is tied up with arbitraging the difference between a country’s current economic reality and its future economic potential.

There are many concepts in this definition of an emerging market that are eminently relevant to digital asset markets, including: stability, legitimacy, protections, and promise. In particular, the key role of sound governance in digital assets is mirrored in the importance of governance in Emerging Markets. The experiment of decentralization in digital assets also calls to mind the experiments in democracy that many emerging markets have gone, or are going, through. These ventures are difficult things to figure out. A solution does not present itself overnight, and even history can’t always serve as a guide, much less a blueprint (i.e. what worked for one developed nation might not work for a developing one). Just as many developing nations have gone through bouts of stability, upheaval, progress, and setbacks, so too will blockchain projects and digital assets. But just as emerging markets have exhibited staying power despite setbacks, so too should digital assets.

The critical element of that staying power is reflected in the last line of Sylla’s definition: the difference between the current state and the future potential. This holds equally true for digital assets, which while facing much uncertainty today, hold great potential. The “current state” for emerging markets in much of the 20th century was ongoing experimentation to find a stable system of governance, enabled by process of law, to empower a stable financial system, to ultimately find a competitive advantage in an increasingly global economy dominated by a handful of superpowers. To achieve such conditions many countries looked to democracy. However, no system of government is one-size-fits-all, and the experimentation created many binary risks as populations voted between differing systems or overthrew existing ones.

The myriad of unsystematic risks across emerging markets made them a difficult investment proposition for private investors, particularly for individuals who lacked in-depth knowledge of these foreign markets and in many cases completely lacked access. Arguably, it was the rise of institutional investors that helped drive meaningful capital flows from developed markets into emerging ones. The core value add of institutional investors was the pooling of risk by many smaller, less-wealthy investors, who trusted the experience and ability of professional investment managers.

However, even institutional uptake of the emerging markets thesis was slow and faced a considerable test in the 1980s when several major developing countries (particularly in Latin America) experienced debt-servicing problems, weakening economies, and volatile economic policies (Chuhan 1994). In 1990, US pension funds, for example, held about 4.2% of their assets in foreign investments. Of this already small proportion, only 2.3% of was in emerging markets. At the time, market participants cited perceived riskiness of the markets, limited information, and illiquidity as impediments to investment (Chuhan 1994), which compounded the existing home country bias of investors in developed markets (Tesar, Werner 1992 and French, Poterba 1991).

Private capital flows to emerging markets increased in the 90s, although further crises tested the asset class, such as the Asian financial crisis in 1997, which saw emerging market equities draw down more than 30-75% in Asia and nearly 30% for EM equities broadly (ICI 1998). Many of the crises faced in emerging markets over the last few decades have revolved around currencies (monetary policy), debt (or more generally access to capital), and banking (financial institutions) – all subjects which have significant impact in the digital assets space as well.

Growth in the MSCI Emerging Markets index over time, compared to global equties market and global GDP. MSCI, IMF.

Despite significant set backs, the size of the EM equity market (as proxied by the MSCI Emerging Markets Index) has grown from $50bn in 1988 to $6.4tn today, and over that period grew from representing <1% of global equities to >10% (MSCI EM as % of MSCI ACWI). Over that time period, a naïve investment in the MSCI EM Index provided an average annual return of 9.4%, compared to 8% for developed market equities (as of May 2023).

Still, investors overall remain underexposed to emerging markets. As of 2021, data on global equity funds suggest investors overall have ~6-8% exposure to emerging market equity (Morgan Stanley IM 2021). An “optimal” allocation is difficult to define, but methodologies such as index weighting, risk/return optimization, and GDP weighting (among others) would suggest allocations of 10-30% depending on methodology (per calculations in Morgan Stanley IM 2021). Allocations to EM by insurance companies are even lower (OECD 2021), but largely due to strict regulatory and liability-driven considerations in their portfolio construction. Pension funds, on the other hand, have meaningfully increased their exposure to EM, from the miniscule amounts quoted earlier, to ~8% in 2021 (OECD 2021). So clearly, the path to acceptance is not yet complete for emerging markets. However, emerging markets are an obvious consideration for every manager of a diversified portfolio, and analysts across banks, asset managers, and hedge funds continue to research and develop the field.

Takeaways

Let us start by saying that our effort in comparing digital markets to emerging markets is one of financial and investment parallels. While inspirational in its own way, we are not trying to equate the establishment of digital assets with the great struggles and sacrifices people in emerging markets have experienced in their path to securing prosperity. However, many of the use cases of digital assets are actually quite relevant to the growth of these economies and the empowerment of their people. The very original motivation of Bitcoin was to create a currency more secure from the failures of fiscal and monetary policy around the world (not just in emerging markets). And since then, many more blockchain projects have built with a truly global audience in mind, seeking to improve structures of ownership, governance, and finance more equitably and accessibly than existing institutions.

The similarity of the financial trajectory, particularly with regard to attracting outside capital, of emerging markets to that of blockchain projects and digital assets is remarkable. The basic problems introducing risks to EM investment are also key issues for digital assets, including regulation, governance, and monetary policy. While complex challenges to face, they do not invalidate the basic thesis on the investment potential of the space.

The EM market has also faced existential threats throughout its history, including government collapses, fraud, defaults, and failed policies, both fiscal and monetary. But the emerging world is not a monolith, and these crises often impacted subsets of markets, with more limited spill over into the generalized EM category. Thanks in part to this built-in diversification, the returns of the asset class have been remarkable, and the benefits to portfolio diversification have been well studied (Tesar, Werner 1992 and French, Poterba 1991).

As we saw with the early, and even intermediate, days of equities – new asset classes can face seemingly insurmountable issues. With time, financial innovations mature and enable the further development of the asset class and the technologies and companies underlying it. With regard to this relationship between financial innovations and the creation of value, digital assets do sit in a slightly more precarious place. Most technologies and economies could initially rely on existing methods of capital access in their nascency and could exist independently of the financial innovations that came to enhance their development. Blockchains as a technology and many projects built upon them, however, very fundamentally rely on cryptocurrencies and tokens to operate. That is, the technological innovation cannot really exist without the financial innovation, and indeed the technology is also the financial innovation. This leads us to one of the primary issues of our time, which is how the unclear treatment of digital assets in a financial sense impacts the adoption and advancement of the underlying blockchain technologies.

Venture Capital

The final asset class we look at is Venture Capital – in many ways the most intricately linked asset class to digital assets. Amongst asset classes, venture capital feels like one of the youngest, but its origins go back to 1946. This history is documented in Tom Nicholas’s piece The Origins of High-Tech Venture Investing in America (2016). He points to the post-WWII period, when members of The New England Council (NEC), which itself was formed in 1925 to promote economic activity in New England, incorporated American Research and Development Corporation (ARD). The goal of the company was to help small businesses get risk capital to finance high-tech innovation. Not dissimilar to today, obtaining such capital from traditional means, such as banks, was difficult, but the founders of ARD saw the potential for long-term value creation and were willing to take the risk.

DEC’s estimated profit and loss statement in their original business plan. Digital Equipment Corporation.

As we have shown for other early markets, the venture capital idea was not a runaway hit. ARD raised only $3.5m of its $5m goal in its initial marketing to investors, and legal constraints limited the involvement of institutions, who were the desired stakeholders. Lobbying efforts were required to make the vehicle accessible to institutions, which did ultimately form a distinctive competitive advantage for the firm at a time when other “private equity” firms were mostly comprised of individual families’ money. ARD was able to intermediate the access to the small, high-potential portfolio companies that institutions were not well equipped to handle. However, the firm struggled to attract capital through the 1950s and saw numerous failed investments among a handful of decent ones. Shares in the closed-end fund traded significantly below NAV.

ARD’s breakthrough came in their late ‘50s investment in Digital Equipment Corporation, a firm specialized in the design and manufacture of transistor-based circuit boards that provided high-powered but cost-effective solutions. This one investment arguably ended up being the spark for the entire US VC industry. As DEC prospered, ARD’s initial investment of $70k for a 78% equity stake in 1957 grew to a fully distributed value of $355mm in 1971 – by far its most successful investment.

ARD’s investment in DEC demonstrated the critical value proposition of venture capital: One could systematically build a portfolio of long-tailed investments; the return of the few that hit the long tail would offset the losses and mediocre gains of the others (Nicholas 2016). This “Power Law” distribution of returns has been the premise of VC firms since, and is also a critical element in the liquid token strategies of Outerlands Capital (see Diversification Part I: Performance).

Interestingly, ARD also got the organizational model wrong. Incorporated as a closed-end fund, it did not have the tax advantages or compensation mechanisms of the limited partnership, which quickly became the favored structure. Despite this, the firm proved to be the proof-of-concept needed to ignite the growth of the industry.

Over the ensuing decades, the growth of the VC market did not come without setbacks. The success of early VC investments such as DEC led to a boom in the 1970s and early 80s that saw the industry expand from just a handful of firms to hundreds, managing tens of billions. Increased competition combined with the inexperience of new fund managers led to inflated valuations, and returns started to moderate. The industry was also challenged by the growth of leveraged buyout firms and growth capital investments. All told, growth in the VC industry slowed and many players exited (Gompers 1994).

The VC industry persisted and got a huge second wind from the advent of the World Wide Web. The revolutionary promise of the internet quickly gave rise to another boom in VC investment, leading of course to the all-too-well-documented dot-com bubble and its eventual popping in 2000. In spite of the crash, many fortunes were made for those who were early investors in the internet, as well as those who had the fortitude to hold through the volatility (see prior section). Venture capital has thrived in recent years, attracting huge amounts of capital to deploy in cutting edge ventures – blockchain projects included. From the few millions that ARD raised back in the mid 20th-century, the VC market has grown to $2.45tn (AUM) globally as of March 2022, according to data by Prequin. Meanwhile, data on Cambridge Associates US Venture Capital index suggests average annualized returns of 28% over the last 25 years, compared to ~8% for the S&P 500.

While obviously the risk profile of venture capital remains high, and there have been notable follies in the past, it remains a highly relevant asset class, seeing increased adoption from institutional investors. A 2020 study by Cambridge Associates showed that allocations to venture capital had increased substantially among endowments and foundations, with a mean allocation approaching 4%, while the top-performing institutions showed even higher allocations – nearing 15% on average.

Takeaways

Participants in the US startup scene may now take venture capital for granted, but its continued existence despite booms and busts, competition and setbacks, is remarkable. Although generally still classed as an “alternative investment”, warranting a small allocation in a diversified portfolio, the asset class has seen uptake by institutions such as pensions since the 1980s . Previously, the mandate to invest with the care of a “prudent man” had limited funds to low-risk investments, but revision in law enabled considerable expansion in risk assets that could provide diversification value for portfolios. We see exactly such potential in digital assets.

Comparatively, investments in digital assets are probably most akin to venture capital investments, and the two share growing pains in the form of optimizing investment structure, a tendency to booms and busts, and the difficulty of valuation. These growing pains are not reason enough to dismiss the investment potential. Unlike venture capital, digital assets, come with the benefit of liquidity and new value-drivers outside of traditional equity mechanics. Just as a wide spectrum of investors has come to see the value of venture capital, so too we believe will they come to see the value of digital assets.

Venture Capital has been successful but is illiquid and difficult to access. The stellar performance of top VC funds means little if they are inaccessible to the average investor, let alone the average institution. In comparison, digital assets promise much higher liquidity and are much more accessible to a wider range of investors. We think of digital assets as very much a “liquid venture capital” style investment, embodying access to breakthrough technologies, like VC, while offering the liquidity more akin to public markets.

Conclusion

In this piece we have examined a fairly substantial subset of the financial history of the modern world, and have shown how early markets are consistently messy, and seldom learn directly from the past. Through the lens of early equity markets in Europe, the proceedings of the 1920s United States, emerging markets, and venture capital we have highlighted ways in which the struggles of digital assets are not new. Our takeaways are thus:

Nascent markets are messy – it does not mean they aren’t worth it

Messy markets do not reflect the actual value of the technology or economies to which they provide access

The structure of financial innovations is less at fault than the behavior of the humans who invest through them

Regulation can help, but investor prudence is critical

We’ve seen almost all of this before, and we can get through it

Digital assets hold revolutionary potential. We’ve expounded upon that at length in our prior work. Much like venture capital though, the distribution of returns has a long tail. Many projects will fail, but diversification can help capture winners and diversify risk.

There is obviously much to be improved in digital asset markets, but the markets are still young. Remember that financial evolution has historically taken place over many decades, generally including bouts of misfortune. Bitcoin is now nearly 14 years old, but the implications and potential of the underlying blockchain technology are still just beginning to be explored. We have moved past a market of just “digital gold” into a market which could be home to the next great technological revolution of our time. As popularized in Malcom Gladwell’s book, The Tipping Point, technological change happens “gradually, then suddenly” (The Sun Also Rises, Hemingway, 1926). In the meantime, the way in which stakeholders can capture value via digital assets is fundamentally new, democratizing, and empowering.

While we wince at the mistakes that participants in digital asset markets have made that so clearly resemble missteps of the past, we are confident in the long-run potential of the asset class, if approached in a thoughtful way. The messiness of early markets is to be expected, and indeed it is the opportunity. Entering a market early and intelligently navigating the maze of risks is how investors can achieve differentiated returns. While we do not argue that any investor should weight digital assets like established asset classes in their portfolio, we believe it is well worth a small allocation, akin to emerging markets or VC. In our next piece we will further examine how digital assets can be positioned inside institutional portfolio.

Footnotes

The organization that evolved into the NYSE was founded in 1792, and the Philadelphia Stock Exchange predates that by another two years. The market also saw various panics throughout the 19th century, linked to collapses in commodity prices, erratic banking policy, and failure of financial institutions.

Conceptually, it makes sense to measure innovation in the lens of intangible capital because innovation can take time to be fully reflected in earnings, but those future cash flows from innovation are what investors discount to arrive at current valuations. Intangible capital, in other words, is a reflection of research and development, which while a cost in the short-term, can lead to significant pay off in the long term.

References

Austin, M., & Thurston, D. (2020, January). Venture Capital Positively Disrupts Intergenerational Investing. Cambridge Associates. https://www.cambridgeassociates.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/VC-Positively-Disrupts-Intergenerational-Investing.pdf

Borowiecki, K. J., Dzieliński, M., & Tepper, A. (2022). The Great Margin Call: The Role of Leverage in the 1929 Wall Street Crash. The Economic History Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.13213

Burhop, C., Chambers, D., & Cheffins, B. R. (2011). Regulating IPOs: Evidence from Going Public in London and Berlin, 1900-1913. ECGI - Law Working Paper, (180). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1884190

Chuhan, P. (1994). Are Institutional Investors an Important Source of Portfolio Investment in Emerging Markets. The World Bank Policy Research Working Papers.

Fisher, I. (1930). The Stock Market Crash and After. The Macmillan Company.

French, K. R., & Poterba, J. M. (1991). Investor Diversification and International Equity Markets. NBER Working Paper Series, No. 3609.

Goldsmith, R. W. (1973). Institutional Investors and Corporate Stock - A Background Study. National Bureau of Economic Research; distributed by Columbia University Press.

Greiner, K. (2023, January 9). US PE/VC Benchmark Commentary: First half 2022. Cambridge Associates. https://www.cambridgeassociates.com/insight/us-pe-vc-benchmark-commentary-first-half-2022/

Harris, R. (1994). The Bubble Act: Its Passage and Its Effects on Business Organization. The Journal of Economic History, 54(3), 610–627. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2123870

Kuhn, C. J. (1937). The Securities Act and its effect upon the institutional investor. Law and Contemporary Problems, 4(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.2307/1189637

Lowenfeld, H. (1910). Investment: An Exact Science. Financial Review of Reviews.

Mosselaar, J. S. (2018, May). A Concise Financial History of Europe. https://www.robeco.com/

MSIM Global Emerging Markets Team. (2021). Emerging Market Allocations: How Much to Own? New York: Morgan Stanley.

Nicholas, T. (2007). Stock market swings and the value of innovation, 1908–1929. Financing Innovation in the United States, 1870 to the Present, 217–246. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262122894.003.0006

Nicholas, T. (2016). The Origins of High-Tech Venture Investing in America . In D. Chambers & E. Dimson (Eds.), Financial Market History: Reflections on the Past for Investors Today (pp. 227–241). essay, CFA Institute Research Foundation.

OECD (2021), Mobilising Institutional Investors for Financing Sustainable Development in Developing Countries: Emerging Evidence of Opportunities and Challenges, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Petram, L. (2021, January 10). What was the return on VOC shares?. The World’s First Stock Exchange. https://www.worldsfirststockexchange.com/2020/10/01/what-was-the-return-on-voc-shares/

Post, M. A., & Millar, K. (1998). U.S. Emerging Market Equity Funds and the 1997 Crisis in Asian Financial Markets. Investment Company Institute Perspective, 4(2).

Preqin. (2022, December 14). Venture Capital Growth to Remain Solid Despite Headwinds — Preqin Global Report 2023. Https://Www.Preqin.Com/. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.preqin.com/Portals/0/Documents/Preqin%20Global%20Report%202023%20Venture%20Captial.pdf?ver=2022-12-14-085541-430.

Rutterford, J., & Sotiropoulos, D. P. (2016). Financial Diversification Before Modern Portfolio Theory: UK Financial Advice Documents in the Late Nineteenth and the Beginning of the Twentieth Century. The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 23(6), 919–945. https://doi.org/10.1080/09672567.2016.1203968

Sato, R., Ramachandran, R. V., Mino, K., & Sylla, R. (1999). Emerging Markets in History: The United States, Japan, and Argentina. In Global Competition and Integration (pp. 427–446). essay, Springer Science + Business Media, LLC.

Smith, E. L. (1924). Common Stocks as Long Term Investments. The Macmillan Company.

Tesar, L. L., & Werner, I. M. (1992). Home Bias and the Globalization of Securities Markets. NBER Working Paper Series.

White, E. N. (1990). The Stock Market Boom and Crash of 1929 Revisited. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(2), 67–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1942891

Williams, J. B. (1938). The Theory of Investment Value. Harvard University Press.

Disclaimer: The discussion contained herein is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice. Nothing contained herein constitutes a solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement to buy or sell any token. Nothing herein constitutes professional and/or financial advice, nor a comprehensive or complete statement of the matters discussed or the law relating thereto. You alone assume the sole responsibility of evaluating the merits and risks associated with the use of any information or content herein before making any decisions based on such information or other content.

Any performance referenced is for informational purposes only and does not represent an actual investment of Outerlands Capital nor does it include any fees related to investing including transaction fees or management fees, among other fees.

As of the date of this publication, Outerlands Capital Management LLC, a Delaware limited liability company, or its affiliates (collectively, “Outerlands Capital”) may hold or advise on long, short, or neutral positions in or related to the companies or digital assets described herein. The information in this website and any materials presented herein (the “Site”) was prepared by Outerlands Capital, is believed by Outerlands Capital to be reliable, and has been obtained from public sources believed to be reliable. Outerlands Capital makes no representation as to the accuracy or completeness of such information. Opinions, estimates and projections in this publication constitute the current judgment of Outerlands Capital and are subject to change without notice. Any projections, forecasts and estimates contained in this publication are necessarily speculative in nature and are based upon certain assumptions. It can be expected that some or all of such assumptions will not materialize or will vary significantly from actual results. Accordingly, any projections are only estimates and actual results will differ and may vary substantially from the projections or estimates shown. This Site is not intended as a recommendation to purchase or sell any commodity or security. Outerlands Capital has no obligation to update, modify or amend this publication or to otherwise notify a reader hereof in the event that any matter stated herein, or any opinion, project on, forecast or estimate set forth herein, changes or subsequently becomes inaccurate. Outerlands Capital may transact in any digital asset or the securities of any company described herein.

This Site is not an offer to sell securities of any investment fund managed by Outerlands Capital or a solicitation of offers to buy any such securities. An investment in any securities or digital assets, including the securities or digital assets described herein, involves a high degree of risk. There is no guarantee that the investment objective will be achieved. Past performance of these strategies is not necessarily indicative of future results. There is the possibility of loss and all investment involves risk including the loss of principal.